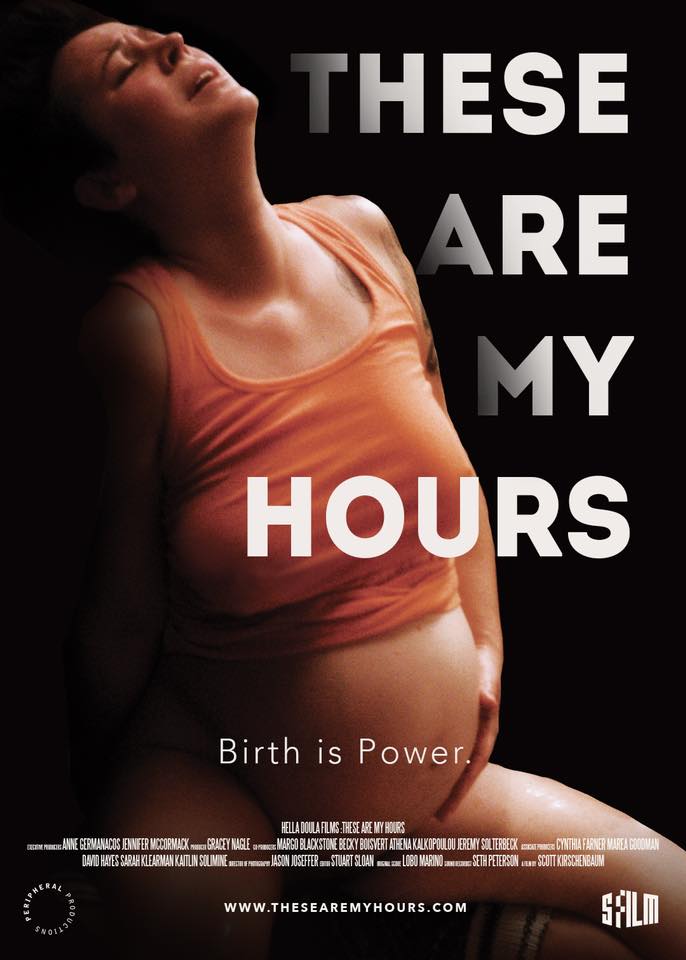

Although it is technically a documentary, it feels a lot more like a fiction film because it tells a single story of a single mother birthing her child. This movie is not about statistics, evidence-based information or public policies.

Instead, watching These Are My Hours is a lot more like actually being at a birth. And not any birth, but one in which a woman takes matters into her own hands and fearlessly rocks her experience, even though at times it seems impossible to do.

I had the honor to chat with Emily Graham, the subject of this film, who shares with us how she got involved in this project, why it is important for her, and what she hopes for the film to do in our crazy world.

M: Tell us, how did you get involved in the birth world?

E: I had my first baby at home almost 10 years ago and I found that after I gave birth I still wanted to read all the books and talk about it and I realized that I was interested in learning about it and working in birth more than just as a mother. So I asked my midwife if I could work with her. Despite me having never trained in anything related to health or birth, she said yes.

|

“My birth work is all about women finding their truth and expressing their autonomy through their birth experience.”

|

When my baby was nine months old, I started attending prenatal appointments and births with her. I worked with her for a few years. I had another baby with her and then I moved to South Carolina, where I live now. I studied with Whapio for two years, doing her holistic midwifery program. My plan at the beginning was to become a licensed midwife. But as I got more experience and of course as I trained with Whapio and heard of her philosophy, I decided that I didn't want to be licensed by the state and I didn't want to practice midwifery the way it is in our culture.

|

E: There were three cameras and two camera operators. The camera that showed the very, very close-ups of the baby and of me, was a long lens camera. The lens is 18 inches long or so, a huge piece of equipment that was on a huge camera on a Dolly. It was very heavy and it rolled around. The operator's job was to do very wide shots and very, very tight shots and he was kind of just out of the room, about 20 or 15 feet from me. He wasn't really in my zone. The shots that appeared to be very close in my face really weren't.

The other cameraman operated the camera that moved with me. He followed me. We were walking through my house and he also had a camera on a rig system that they installed on my ceiling in the living room. It was on a wheel so it could roll back and forth and up and down. The camera itself was on some sort of machinery that would allow it to smoothly move up and down and it could go all the way down to the floor. The cameraman operated those. He was as close as a doula might be. He was closer to me than anybody else. Whappio came to meet the crew and she had a little meeting with everybody and she told them about altered states of consciousness and she told them the holistic stages of labor, the story of birth. This was so they would be prepared for what might happen. And she said, “The only thing Emily can do is follow her labor and the only thing you can do is follow her. That's it. Just have your equipment ready and do those two things that it'll work out.”

E: Scott took Whappio's doula training in California and he had not seen a birth before we made the movie. He worked at seeing births. But people had a hard time with him being a guy and eventually a bunch of us women said to him, “you don't need to see a bunch of births. You just need to get to know Emily. Other people's births won't tell you how she'll birth. You need to see very many births to understand the overall picture of birth. You're not going to see that many. So just get to know her. She'll tell you what she will do. She knows herself.” So he decided to listen to us and, and do that. And most of the crew had not seen a birth. One of the cameramen had worked on a reality show that did birth in the hospital; I think it was one of the teenage birth shows on MTV or something. So he had seen birth that way. And one of the other crew members had seen his own child born by Cesarean. Nobody else had ever seen a birth before.

|

M: Do you think they were nervous? If they were, it didn't seem like it affected you.

E: The crew really had a lot of trust in me. Part of it is that I had had children before and had babies at home before. And also I told them what to expect in terms of what I know of how I birth. I knew that it would be pretty fast. I knew that it would be pretty loud. I knew that I wanted to go near the fireplace and that I didn't want anyone to touch me or talk to me. There were certain things that they expected and they could see as those things were unfolding “Oh, this is like she said.” So I think they were able to relax a little bit. I thought it was actually kind of fun to invite a bunch of people, especially a bunch of men to come see birth in its wild form. It felt very much like the elder teaching her community about something essential, sharing some secret with people that might never get to stand in the room while someone really roars their baby out to under their own authority. That's not something very many people get to do and it felt very good to offer that to them. Especially the men. |

“It was actually kind of fun to invite a bunch of people to come see birth in its wild form. It felt very much like the elder teaching her community about something essential, sharing some secret with people that might never get to stand in the room while someone really roars their baby out to under their own authority. That's not something very many people get to do and it felt very good to offer that to them. Especially the men.”

|

E: I didn't really have many fears. I did keep it in my mind that it's possible that something could go wrong and that something could go horribly wrong and I could die. It's not likely, but I know that that's a possibility. Always. I know that's why birth is so big, it's because you go out to the edges of life and death. So I did talk with the director about that. I said, “I'm not going to go to the hospital unless I need someone to save my life. I'm not going to go for pain relief or whatever. But if I go, it's because I am really going to be desperate for the doctors to save my life. And if that happens, you can't come.” It was hard for them to hear that. And I said, “if I die, I don't want you to show that as a film. Out of respect for my family.” That was really hard for them to talk about. They also know it's a possibility, but I think it was hard to listen to me saying that while I was pregnant. I think it was really good for us to get through that discomfort. That conversation helped us grow closer. My husband and the director and I were having ice cream one day and talking about that and you know, I think it's necessary to be able to have these conversations. I was able to really express myself fully. We were able to have uncomfortable conversations together and come out the other side as a group. That's what we do as doulas, right? We get to know people, they're allowed to tell us that they're afraid of dying or they're afraid of mothering the way their mom mothered them, or they're afraid that they'll never have sex again. We want to be the kind of person that they can say all of that stuff to. So that if it comes up in labor, we know it, or maybe it doesn't have to even come up in labor because they've already said it. And if he was going to be there and he and his team were going to be as close to me as a doula was, I needed to be able to be myself that deeply. We did a lot of that kind of talking, the director and I, he saw a lot of my raw emotions over the couple of years before the filming.

M: During early screenings, people were describing the film as very intense. What do you think they mean by it?

E: Since we have added the score, that comment has shifted and people do find it intense, but I don't think that they say it with the same gravitas as they used to. The composer, Lobo Marino, is this couple that plays music together and they watched the film a few times to get familiar with it. Once the picture was locked they improvised the music as they watched the film. They played music at the moment that felt the mood of what they were seeing, which is why it's so beautiful. I think that has helped people understand how to feel or how to hold their emotions. It can feel so big that they don't know how to contain it. I think it is because people are not used to seeing birth and it is so big. It makes you think about life. Like, "this is me, that's my mom. That's every human on the planet." It can just expand so big in a flash. But early on, the intensity was mostly focused around the concept of me being isolated because I liked to birth alone. Of course, I had more people than most people really have in the room with them. But I don't want anyone on me or next to me or to touch me or give me affirmations or to give me massages. I just liked to be left alone. Most good photos of birth are of people getting love from other people because it's so touching to see. Because the camera was so close to me, it was just me in the frame and everyone that was there is kind of out of the frame a lot of the time. My husband was always in that chair where he was. He stayed right there the whole time just waiting for me to need him when I did. He came and then when I let go he would sit down again and wait. But most of the time you can't see him because the camera is focused on me. It does feel like I'm just here alone and everyone has left me. It's been really interesting to think about that because I wonder why we are still stuck on this idea that women can't manage it on their own. Even if they did leave me, that wouldn't make it too intense. I'm giving birth to a child. I'm very, very powerful. Don't need to be stroked necessarily or to be told I'm doing a good job, that's not necessary. Sometimes it's what a woman wants, but our culture doesn't like to acknowledge that a woman can be naked and vulnerable and spitting and pooping and dripping and ugly and still be powerful. That challenges a lot of what we believe. I think it was a pushback, an unconscious decision to call it too intense because I think it calls into question everything we believe about women.

|

“Our culture doesn't like to acknowledge that a woman can be naked and vulnerable and spitting and pooping and dripping and ugly and still be powerful. That challenges a lot of what we believe.”

|

E: I feel like I was totally freaking out. I look a little bit like I'm freaking out in some moments, but there was a lot more happening in there. I was trying to understand what could I do, how could I move, how can I breathe, how can I make myself get through this moment? I was really struggling to find something that worked. But I can't see that in the picture that they have captured. It looks like I'm just working hard. And I was. My baby was born in a funny position. She was born facing the side instead of facing down. So it was hard to push her through my bones because she was not in optimal positioning. I had to push a lot harder than you would expect a fourth-time mom to push. I pushed harder with this baby than any of my others, including my first. And it took longer. She was only an inch or so in but wouldn't move for maybe an hour. I was really trying a lot of different things. That's why I moved and got into like funny backward positions, shifting so much, trying to find the right place to give her a room. So I felt like I was failing at times to understand what to do and I look kind of in control in the picture that I see, I look like I'm just following my body, which I guess I was, but it felt harder to do in my body then it looks.

M: How did you decide to make this film and what made you feel committed?

E: At first, I did it because I thought it was really interesting and very cool and I like adventure. So I thought, sure, let's do that. But I was asked all these questions and the more I heard myself talk, the more I thought this is a chance for me to really say something about birth in a way that different people can hear it because it's a different form of art, it will touch some people that wouldn't be touched by reading a birth story or reading a book. This will touch people that hear things in a different way. I became more dedicated than anybody else I think. And now I've become part of the post-production team because it became so important to me. Not that it's my birth, but that it is a declaration that birth is worthy of a film, of art, of being seen by people who are not into birth, that birth is the story of humanity. That it's not a joke. It's not a silly slapstick piece of a story. The way that it is in media now says about women that we are kind of crazy and we don't know what to do with our bodies and we need people to save us. That we're gross. I really wanted this film to tell the other story and it just happens to be me who's giving birth in the film. It's almost like there are two parts of it for me. One is the emotional gratitude that I have that my family gets this amazing gift of our birth being on film. But the other part of me, it is just a film about birth and me working for the film is kind of like me saying, "let us use this film as an inspiration for a new conversation about birth."

E: I'm very sensitive to that. I don't want to feel like I am like proselytizing home birth or undisturbed birth or whatever. I do understand that the physiology and the hormones of birth work optimally when in a setting like I had. Knowing that some people can't do that or don't want that and that, that's okay. But I do want people to see that you don't need to have that safety net. Just because it looks hard and it is painful it doesn't mean that it's wrong. It's okay to expose the vulnerable parts of yourself during birth. Not that this is a “how to birth”. Not at all. Or even a home versus hospital. I think people know that there are options and if they don't, I hope like hell that someone tells them that there are. I just want to remind people that birth is about a person, a family having a baby and it's not about the caregiver. I could have had any caregiver there or no caregiver there. It's not about that. It's about how do we return the birth story to the family and how do we honor that story. Even when it has messy bits, even when I look ways I don't want to look or do things I don't like or don't handle myself well. It's still worthy of having a feature film made about it.

|

“Just because it looks hard and it is painful it doesn't mean that it's wrong. It's okay to expose the vulnerable parts of yourself during birth.”

|

The director calls it the heroine's journey, the hero's journey. We talk about that and there's so many films and books and plays and everything about the hero's journey, how he goes alone and, and he has all of these trials and challenges and people come to help him, but then they leave and he has to go alone. And then he comes back, a transformed man and he shares with his community what he has learned and now he is changed. His status has changed and all I'm trying to say is birth that too. And I want to share with you what happened when I took my journey.

|

M: Do you think this film can be scary for some people?

E: If you really want your birth to have no pain and you were looking for confirmation of that, I could see that it might make you scared. But it's very clear in the film that the moment I give birth that it's over. You watch that happen and you tell women “it'll end. I promise it'll end. It'll just be over when you give birth.” And that's hard to contextualize if you don't know. But to see my face, I turn and I smile at my husband, I'm filled with the most intense joy I've ever felt in my life at that moment. And it's been 30 seconds since I was like “roar!” It can shift just like that. And I think it strikes people like, “oh yeah, it is hard. And then look what she gets.” The elation you feel when the baby has come out, and the rush of oxytocin and the gratitude that it's over. There's a challenge, there's pain, and I don't know if you could call it pain intensity, whatever it is in your mind. I'm not afraid of calling it pain, but I can see why some people don't call it that because it's not quite like pain. I don't necessarily advocate not calling it pain because I don't think that there's something wrong with enduring pain. For me, it's a marker of what I have done to have endured that. If it was easy, it would not be as meaningful for me. And I don't think everyone should feel that way. People want to have ecstatic births with orgasm. They totally should. Sounds very fun. But for me, I need my rite of passage to have a certain amount of discomfort for it to feel real.

People that are pregnant are going to have to go into labor and they're going to see what it's like. I don't really see a point on hiding from them that it's going to be intense, really intense, like maybe the most intense than you can imagine ever happening to you.

There were a lot of people who've I've been to their birth and they were doing the thing where they're like freaking out, especially internally and, and I was saying things like “you're handling it beautifully. This is just what it's like. This is what everybody does. This is what everybody feels. You're doing amazing.” And they're like, “I don't believe you. I'm really freaking out. I'm the worst. I'm so bad at this. I need an epidural.” Well after they've watched the film, they've said to me, "you're really right. I wished that I had seen this before because now I know that I was handling it fine because I was handling it like you did and you had your baby. That was just part of the process." And often people at the hospital tell women “You really look like you're in a lot of pain. We can take care of that.” And oh my gosh, in that moment, who's gonna say no? (Some people do and I think they are amazing.) But if you had seen this film, you know when it gets like this you're nearing the end, and it's going to look and feel crazy. When you get to that point and they say you're in a lot of pain, maybe you need an epidural, you might think “I'm just getting close to having a baby now. I am handling well. I'm really doing it. I'm getting close to birth. I'm going to push my baby out. I'm getting there.“

That's what I hope.

|

M: How would you hope this film is going to change or shift the birth world?

E: My hope is that girls can grow up to not have to undo their beliefs about birth. I love that you said this is a normal birth because there was a young woman on the film team who was from New York City. She had no children and she expected to be really grossed out by the birth. She came out into the room right before the baby was born and kind of watch her be born. And she said, really the thing that came up for me when I thought about later is that it just seemed so normal. The whole thing just seemed so normal. |